I recently visited the Beechcraft factory in Wichita to pick up a new G36 Bonanza and fly it and its buyer to a paint shop at Moline, IL (KMLI) for a custom scheme. As you can see from the photos, the airplane was delivered as a blank canvas, with a base coat of the standard Beechcraft Matterhorn white. When finished in a couple of weeks, it will be stunning, with red, silver, and black accents.

The basic airplane is an update to the classic A36 (BE36) model that Beech has sold for several decades. I have owned a 1989 A36 (lately with updated avionics) and instructed in Bonanzas for many years. The key differences that distinguish the 2013 G36 from previous models are:

- The Garmin G1000 integrated avionics suite, now including WAAS capability

- A car-like climate control system (heat and air conditioning) that can be used during all phases of flight, including takeoff and landing

- Enhancements to the interior

- LED lights, inside and out

Like early G36s, the latest iteration includes dual alternators, buses, and batteries that eliminate the need for a pneumatic system to drive mechanical gyros. The standby instruments are all electric.

We arrived at the Beechcraft delivery center early on a Friday morning to inspect the airplane and take it for an acceptance flight. That local hop, with a Beech production test pilot along to supervise, went fine in the brisk prairie winds, turning up just a few rattles and cosmetic details that needed attention, which a team at the factory immediately set about correcting. The delivery process involves many steps and much paperwork, so while the owner dealt with all that, I checked the weather and considered the routes I had previously plotted from KBEC to KMLI.

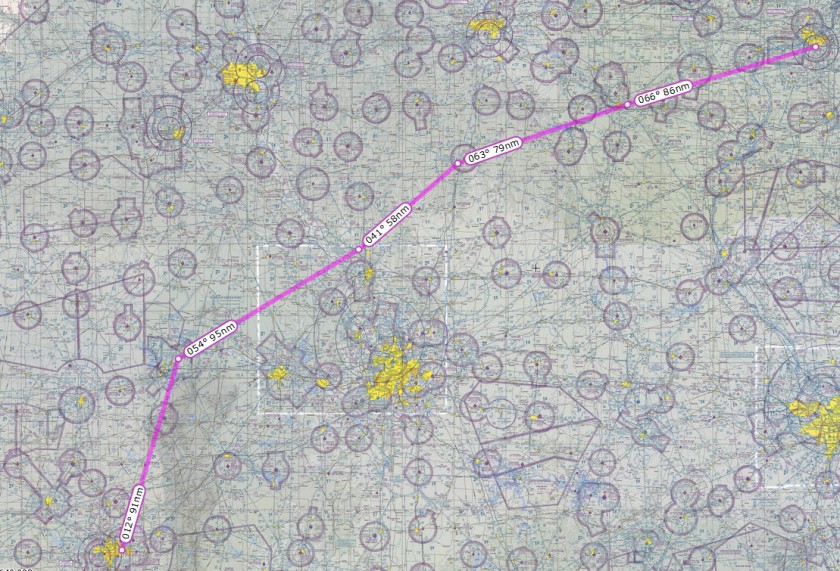

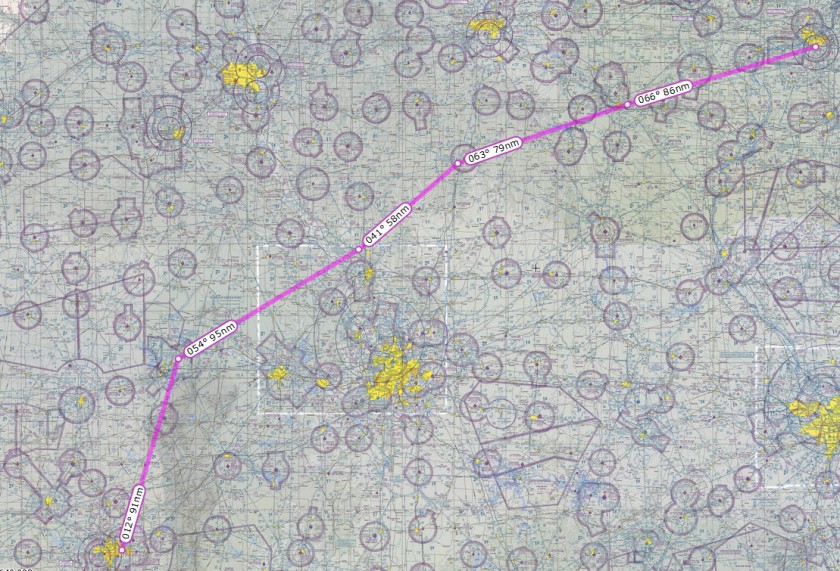

I had hoped to fly a reasonably direct line, with a short dogleg to avoid the airspace around Kansas City (KBEC EMP V10 IRK MZV KMLI), but the weather in the Midwest in December doesn’t respect a pilot’s wishes. And when I fly a new airplane, I insist that the first couple of legs must be flown during the day in VFR weather. After talking to a flight service briefer and analyzing the situation with various computer flight-planning tools, I came up with plan B—aim north first and fly a dogleg to the west and north of a stationary front that blocked the direct path with reports of low ceilings, ice, and freezing rain.

The weather at and around KMLI was still good VMC, with a ceiling of 8500 feet and at least six miles visibility, and it was forecast to remain basically unchanged at our ETA, a little after 4:00 p.m. local (sunset was about at 4:30 local time). The good news: we’d have brisk tailwinds helping to speed us along most of the way.

After lunch and many handshakes, the owner and I climbed aboard about 1:30 p.m. MST. Because the new owner, who has spent the last several years flying helicopters, hadn’t had time to get training in the Bonanza or the G1000, I took the controls for the flight to The Quad Cities. I will check him out in the aircraft after I ferry it back to the Pacific Northwest.

Our revised route (KBEC MHK STJ LMN OTM KMLI) penciled out to about 400 nm and about 2:30 ETE. Because there were airmets for ice and other unpleasantness, I did not file IFR—I wanted flexibility to maneuver as necessary to remain out of the clouds. And with a brand-new engine up front, I did not want to climb to an altitude where we wouldn’t be able to maintain the relatively high power settings recommended for breaking in a new powerplant.

We started low beneath across the Kansas farmland beneath an overcast, hurried along by more than 30 knots of tailwind. Fortunately, it was smooth, and as expected, we soon encountered scattered clouds that let us climb to 7500 ft above mostly thin, scattered, occasionally broken, clouds, with a similar layer a few thousand feet above us. We had good visibility aloft, and despite the flat afternoon light in the low December sun, we could see the snowy ground much of the way. The onboard XM weather display is a vital safety feature on such trips, however. We could monitor weather reports for airports along the route and our destination, keep an eye on alternates, and track the slow progress of the front as we flew around its perimeter. Knowing that we had good alternates always just a few minutes away (the Midwest is blessed with an abundance of airports), and not having to weave around or through high terrain (the otherwise boring flatness of the Midwest is also a blessing this time of year) made the trip mostly stress-free. Of course, I was only the pilot—I hadn’t just signed paperwork for an expensive new airplane.

By the time we approached Moline, however, the ceiling had dropped. So I requested a popup IFR clearance for a descent. Quad Cities Approach quickly issued a descent clearance, and we dropped through the thin layer of stratus for a visual approach. The visibility remained about six miles, which, if a bit limited for those of us accustomed to the vistas of the western skies, is standard VMC for much of the eastern two-thirds of the country. I had loaded an RNAV (GPS) approach into the G1000 to help us stay lined up while we waited for the runway to appear in the late-afternoon gloom. After about 2:45 minutes en route, we were down and clear in cold Moline. The ramp crew, bundled in multiple layers of arctic gear against an icy wind, quickly got the plane into a hangar while we waited in the warmth of the lobby at Elliott Aviation, the top-notch, full-service, and friendly FBO at KMLI.

The airline trip home via Minneapolis wasn’t nearly as pleasant, but that’s another story. I’ll return to Moline in a few weeks to pick up the airplane and fly it to its new owner near Seattle. I hope to have time on that trip to take more pictures and provide more details about the airplane. I’ve made similar ferry flights from the Midwest many times over the years, but never in a factory-fresh Bonanza. It should be an interesting experience.