All instrument pilots learn the rules (14 CFR §91.185) that apply if you lose two-way radio communications while operating under IFR. But most discussions of that regulation overlook three key paragraphs in the AIM and their practical implications.

Note: This original text for this post first appeared in the February 2018 issue of the American Bonanza Society magazine.

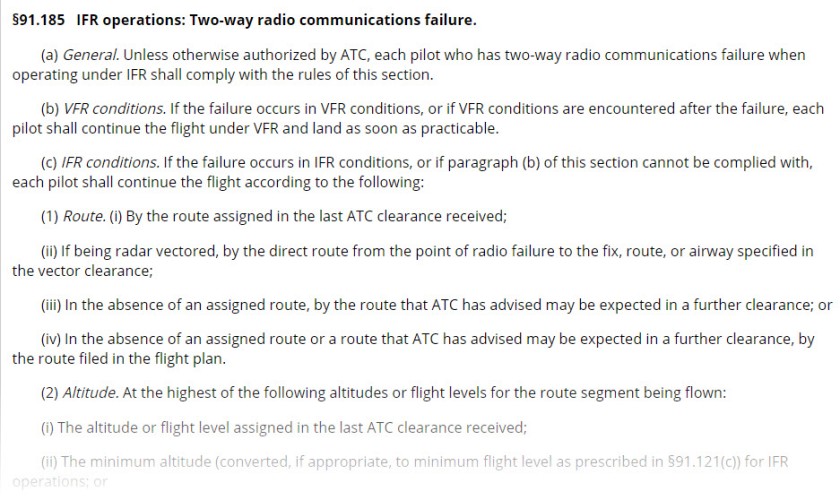

First, to review the basics, see 14 CFR §91.185 and the Instrument Flying Handbook (FAA H-8083-15B), which describes the details of the regulation in “Communication/Navigation System Malfunction” (p. 11-8).

To simplify matters, most of us employ a mnemonic such as Avenue F MEA to aid recall of the key details of the route and altitude to fly (assuming you are not flying in VMC, do not encounter VMC after losing two-way communications, and that you cannot hear or respond to ATC via voice over a navaid, squawking IDENT, turning to headings, or other means).

Avenue F (Route)

- Assigned: Last assigned heading, or—

- Vectored: Fly the last vector to the ATC-specified fix or route, or—

- Expected: Fly the route ATC last told you to expect (e.g., join an airway, feeder route, localizer, etc.), or—

- Filed: If you haven’t received an updated clearance or route from ATC, fly the route that you filed.

MEA (Altitude)

- The minimum en-route altitude for the segment of the route you’re flying, or—

- The expected altitude ATC told you to anticipate, or—

- The assigned altitude that ATC included in your original clearance

To the route and altitude, add timing, so that you arrive at your intended destination when ATC is expecting you, per the details in the regulation and the AIM.

To these guidelines, I add the specific lost communications procedures that are typically included as notes for published IFR departure procedures. For example, see the chart for the YELM THREE departure at the Olympia, WA (KOLM) airport.

Practical Advice from the AIM

Instructors and DPEs enjoy posing lost-communications scenarios that require careful parsing of 14 CFR §91.185 and scrutiny of IFR charts.

But in focusing on the regulation itself, we often overlook what is arguably the most important practical guidance for such situations, found in AIM 6−4−1: Two-way Radio Communications Failure.

The first three paragraphs of that section note that:

a. It is virtually impossible to provide regulations and procedures applicable to all possible situations associated with two-way radio communications failure. During two-way radio communications failure, when confronted by a situation not covered in the regulation, pilots are expected to exercise good judgment in whatever action they elect to take. Should the situation so dictate they should not be reluctant to use the emergency action contained in 14 CFR Section 91.3(b).

b. Whether two-way communications failure constitutes an emergency depends on the circumstances, and in any event, it is a determination made by the pilot. 14 CFR Section 91.3(b) authorizes a pilot to deviate from any rule in Subparts A and B to the extent required to meet an emergency.

c. In the event of two-way radio communications failure, ATC service will be provided on the basis that the pilot is operating in accordance with 14 CFR Section 91.185. A pilot experiencing two-way communications failure should (unless emergency authority is exercised) comply with 14 CFR Section 91.185….

Note also that the Instrument Rating ACS places lost communications procedures in section VII Emergency Operations. The standards for Task A in that section state that you must understand and demonstrate the:

Procedures to be followed in the event of lost communication during various phases of flight, including techniques for reestablishing communications, when it is acceptable to deviate from an IFR clearance, and when to begin an approach at the destination.

The AIM text recognizes and implicitly suggests several issues that you must consider if you lose two-way communications while operating IFR in IMC. For example:

- What caused the communications failure? Just broken radios? A fault somewhere in the electrical system?

- Will proceeding according to the regulation require you to continue the flight–perhaps for an extended time–over potentially hazardous terrain or through challenging weather?

- Are you currently operating within or near busy airspace, such as Class B? Will your cleared IFR route take you near or into such airspace?

Suppose, for example, that you lose communications after you level off westbound following a departure from Spokane International Airport (KGEG) in Washington state en route to Boeing Field (KBFI) in Seattle.

Your clearance will take you via V2 across the Cascade Mountains to Boeing Field (KBFI) in Seattle. You are not on fire or aware of any other issue with the airplane that demands an immediate precautionary landing. Weather at airports along or near your route is IMC but at or above published minimums for the approaches available to you.

Adhering to the letter of 14 CFR §91.185 would require you to continue along your last cleared route at the appropriate altitudes to arrive as close as possible to your ETA at KBFI.

But the introductory paragraphs to AIM 6-4-1 give you broad support to exercise your emergency authority as PIC.

For example, diverting to an airport such as Moses Lake (KMWH) and flying one of its many available approaches would be far more reasonable than continuing across the mountains and then descending into the congested airspace that surrounds Seattle—and perhaps holding near KBFI to arrive near your ETA.

Whether or not you continue strictly according to the regulations, ATC will clear the airspace around you until your intentions are clear and they’re able track you or confirm that you’re on the ground. Assuming that they can still observe you—even if only as a primary target on their traffic displays—they will be happy to watch you descend into a relatively quiet airport like KMWH rather than, like members of a curling team, furiously sweep the path in front you all the way to your filed and cleared destination.

Earlier today I received an email on this very topic. In terms of filed ETA, it poses the question: what would you do when the failure occurs close to your intended destination? This free video makes a case to forego any holding and to land as soon as practical (under a lost comm emergency), especially in congested airspace.

https://www.pilotworkshop.com/8-18-mastery-video

Would you agree with this conclusion Bruce? Thanks, Scott

Yes, for the reasons I outlined in my article. You have broad authority to exercise your emergency authority. No one wants you holding 45 minutes in busy airspace. You aren’t sure what caused the communication failure, etc.

Could you discuss this route in the other direction? BFI-GEG via Kent 8, V2. You lose comm approaching ZIGED. How do you get to V2 while assuring terrain clearance? Would you go to SEA first (with an MCA) and then on course? Etc. Thanks

If I were departing the Seattle area IFR in a typical piston single en route to any destination across the Cascades, I’d definitely exercise my emergency authority, regardless of the actual cause of the communications failure. The action that I’d take would depend on available alternates, my position and the conditions I was flying in at the time of the failure, etc. I certainly wouldn’t continue the flight all the way to KGEG per the letter of the regulation. As to my route and avoiding terrain, like most IFR pilots these days, I fly with an iPad and an IFR-approved GPS (with synthetic vision) in the panel. Determining my position and proximity to terrain isn’t difficult, so I could find a way to a fix that begins an approach.

Lost comms is not necessarily an emergency, is it? So you’re not necessarily exercising your emergency authority as PIC. Given the possible disconnect between FAA’s interpretation of the regulation and the reality of flight in IMC, and between what the regulation strictly requires and what might be safe, what could be our possible exposure to enforcement action if we decide not to hold for 45 minutes in busy airspace? It’s smart not to hold. ATC really doesn’t want you to. How about the regulators?

See the AIM paragraphs quoted in the original post:

a. It is virtually impossible to provide regulations and procedures applicable to all possible situations associated with two-way radio communications failure. During two-way radio communications failure, when confronted by a situation not covered in the regulation, pilots are expected to exercise good judgment in whatever action they elect to take. Should the situation so dictate they should not be reluctant to use the emergency action contained in 14 CFR Section 91.3(b).

b. Whether two-way communications failure constitutes an emergency depends on the circumstances, and in any event, it is a determination made by the pilot. 14 CFR Section 91.3(b) authorizes a pilot to deviate from any rule in Subparts A and B to the extent required to meet an emergency.

The current AIM says squawk 7600 (not 7700 / 7600 like we used to do in the old days)…so to NOT follow the requirements of 14 CFR §91.185 (two-way radio comm failure procedures) and avoid enforcement action, you need evidence that you declared an emergency; and that evidence is your 7700 / 7600 alternate squawk code. Or just squawk 7700 and ATC will know you have had two-way radio comm failure, since they can’t communicate with you. IMHO if you squawk only 7600, you have not declared an emergency and you MUST follow §91.185 to avoid enforcement action. Your thoughts?

I doubt that failing to use code 7700 would in itself result in enforcement action.

I agree Bruce; but it’s our only evidence of exercising emergency authority, right?

It’s one piece of evidence. The others would include your actions and statements to FAA after the event.